Long-term electric vehicle projections make it seem as though transitioning to an electrified transportation system is a foregone conclusion, when in reality it will not be easy or cheap.

The Center of American Progress (CAP) highlighted this point in a recent report. “Tipping the balance of vehicles toward PEVs requires the funds to incentivize the widespread adoption of new vehicles and their charging infrastructure, along with the will to overhaul the existing system,” it states.

Policymakers need to find new and creative ways to put more plug-in electric vehicles on the road, according to the report. Expanding EV infrastructure is a major component of that. Policy leaders across the country are investing in charging stations through the use of state financial incentives and funds made available through the Volkswagen settlement, but CAP argues that those initiatives are not enough.

State legislators, state departments of energy and transportation, and state utility regulators all have roles to play in the electrification revolution. Then there’s the matter of managing this change. Plugging millions of EVs into the electric grid represents both a challenge and opportunity for utilities. In failing to take action, power companies risk being overrun.

The next three State Bulletins will dig into the latest EV policy research to provide an in-depth look at the EV policy landscape today. Part One, continued below, examines the need for EV policy action and possible policy solutions. Part Two will focus on utility regulation and how to design programs that support EV growth in a way that benefits the entire grid system. Part Three will take a closer look at what some utilities are already doing to encourage — and take advantage of — EV adoption.

(Click here to read Part 2 and Part 3)

The need for stronger policy drivers

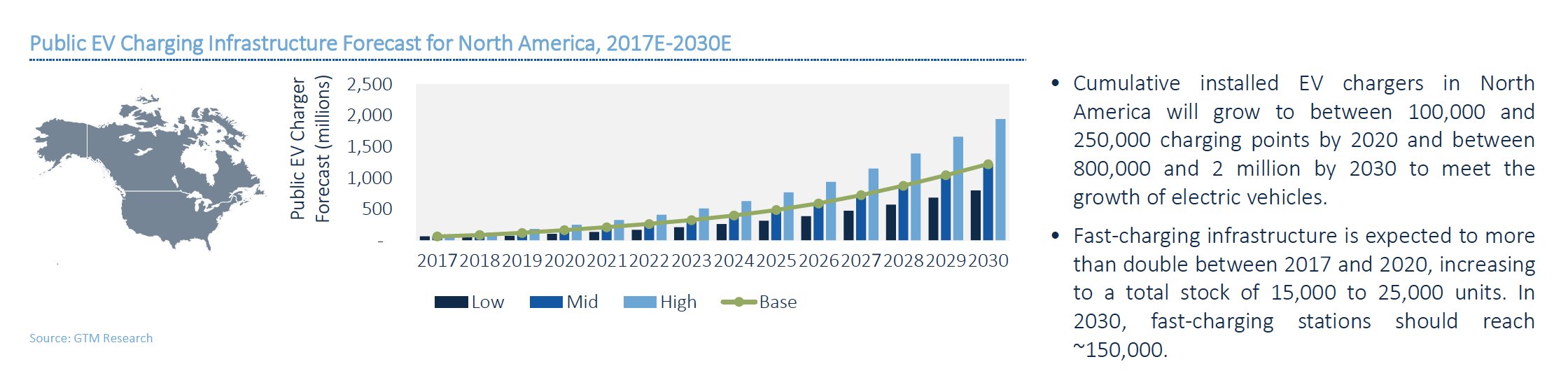

The pace of EV adoption and EV charging deployments is accelerating. In its recent EV Infrastructure Development report, Wood Mackenzie analysts forecast cumulative installed public EV chargers in North America will grow to between 100,000 and 250,000 charging points by 2020, and between 800,000 and 2 million by 2030.

This expansion will be driven by rapid EV growth, which is being facilitated by falling battery prices, the expansion of ridesharing and the proliferation of low-cost sensors, among other things. But the number of charging points ultimately installed won’t depend only on these market factors, but also on policy drivers.

High capital costs and limited utilization make EV charging a tough business. As a result, government subsidies and stakeholder partnerships are key to spreading the capital costs across multiple stakeholders, according to Wood Mackenzie. There are also regulatory hurdles that prevent or slow utilities from building out EV charging infrastructure, “including the slow speed of the process, business-case complexity, uncertainty regarding the scale of regulated utility investments vs. free market investment, and fairness of cost absorption by customers,” the report states. Overcoming those hurdles requires collaboration and partnerships between multiple stakeholders, often over long periods of time.

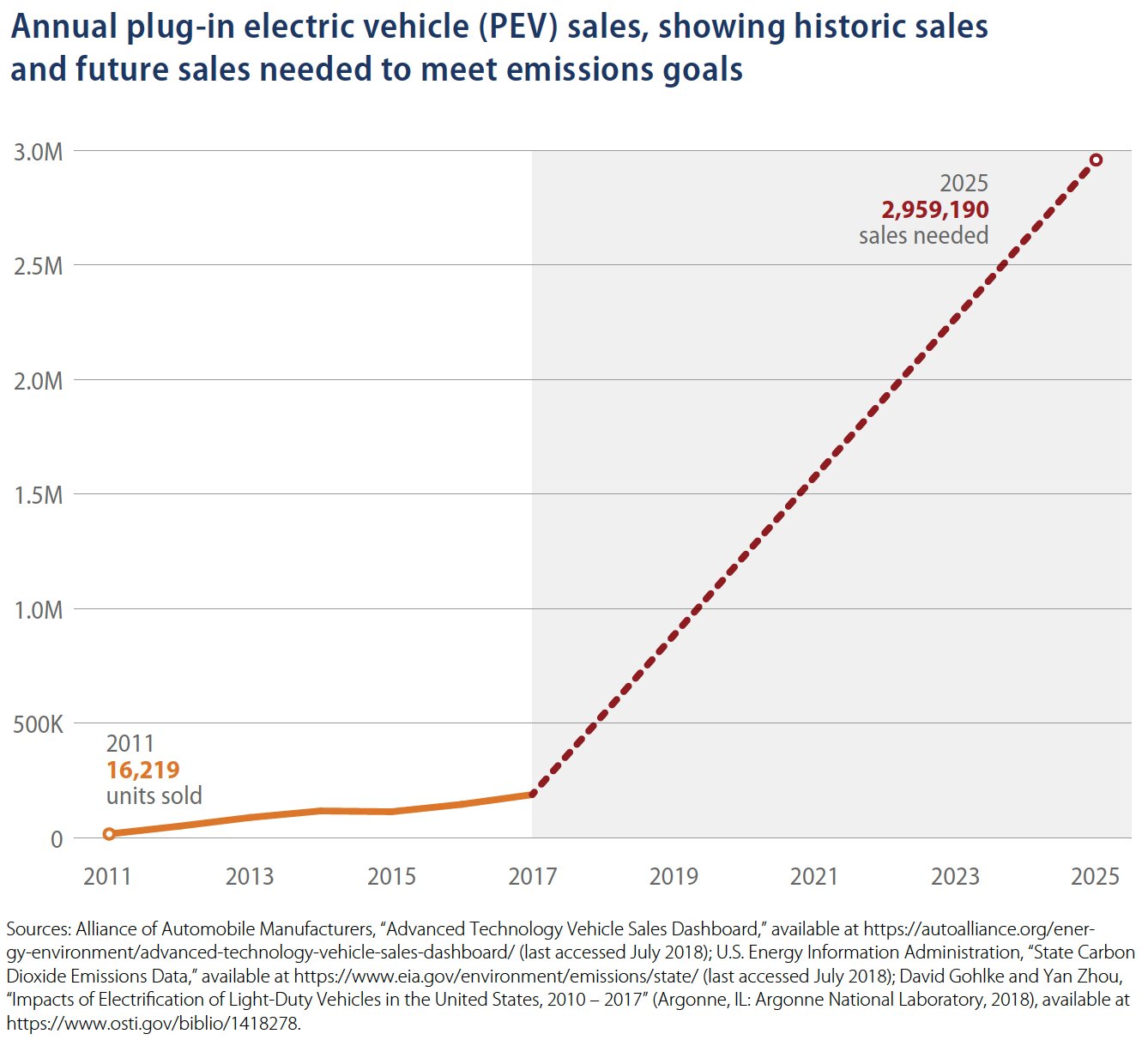

According to the CAP report Investing in Charging Infrastructure for Plug-In Electric Vehicles, the U.S. needs to add an estimated 14 million new EVs and more than 330,000 new public charging outlets by the end of 2025, in order to meet its Paris Agreement targets. For comparison, there are roughly 800,000 EVs and 18,000 charging stations on the road today, according to data from the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers and the Department of Energy.

Under the Paris Agreement (which President Trump is working to repeal), the U.S. committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions 26 percent to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. In 2016, the transportation sector was responsible for 28.5 percent of U.S. emissions — and for the first time it surpassed electricity to become the largest source of U.S. emissions. Light-duty vehicles (LDV) have consistently made up about 60 percent of the transportation sector’s emissions.

To estimate the number of PEVs needed to achieve emissions reduction goals in the LDV sector, CAP relied on a 2018 report by the Argonne National Lab that estimated carbon dioxide emission savings from EVs as compared to internal combustion engine vehicles. To calculate how many charging stations are needed to accommodate these vehicles, CAP used the U.S. Department of Energy’s new EVI-Pro Lite tool.

States that have signed on to the memorandum of understanding committing to coordinated action on their zero-emission vehicle programs, as well as those participating in the Regional Electric Vehicle Plan for the West, are already making progress toward the deploying the infrastructure that CAP determined they will need by the end of 2025. These efforts “demonstrate that concerted policy efforts can produce results,” the report states. Still, it’s not enough.

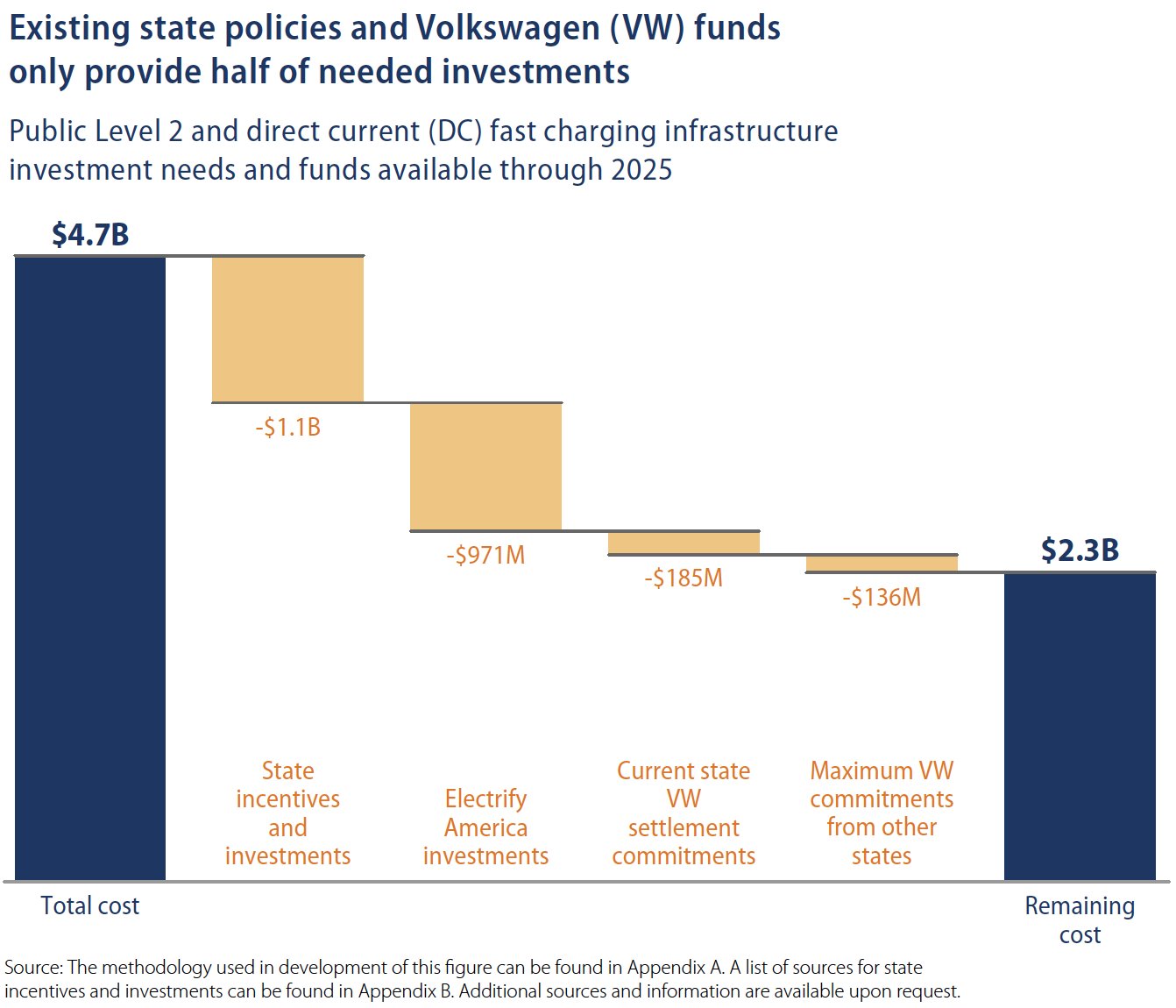

Based on CAP’s analysis, existing state and Volkswagen funds can provide only about 50 percent of the funding needed to deploy adequate public charging infrastructure through 2025. That leaves a $2.3 billion funding cap that additional public resources and private investment are needed to close.

State and local policy options

To fill the $2.3 billion investment gap, CAP offers the following policy recommendations for state policymakers.

Work with state legislatures to provide financial incentives for charging infrastructure. California is the shining example of this. In fiscal year 2017, California allocated $17 million to charging infrastructure and will spend about the same in fiscal year 2018. California isn't the only state investing in EV chargers, however. Maryland, for instance, covers 50 percent of DC fast charger project costs, up to $60,000 with a maximum amount of $500,000 through fiscal year 2019. Overall, 17 states have a financial incentive that lowers the cost of public Level 2 and DC fast chargers for installers.

Join or start a carbon pricing program that generates revenue that could be used for charging infrastructure. Delaware, for example, is a member of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and uses a portion of the money it receives to offer rebates and a grant program for chargers.

Direct state departments of transportation to consider ways to incorporate charging infrastructure into their investment plans. State departments of transportation could potentially use their share of the Federal Highway Administration’s Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program funds, which are typically used to improve traffic flow and transit options, to invest in EV charging infrastructure. The North Florida Transportation Planning Organization used $450,000 of its CMAQ funding to expand a network of Level 2 and DC fast chargers.

Apply for federal grants for charging infrastructure. States can apply for funding through U.S. Department of Transportation’s Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development Transportation Discretionary Grant program, formerly the TIGER program.

Work with utilities to provide financial incentives for and to invest in charging infrastructure. Utilities are expected to play a key role in building out EV charging infrastructure (more on this in Part 2). State policymakers should engage with utilities and eliminate any regulatory barriers that may limit their investment. In one recent example, Ohio regulators approved a rate plan for American Electric Power Company that allows the utility to provide rebates for the deployment of 300 public Level 2 charging stations and 75 DC fast charging stations.

The private sector will be an integral partner in states' efforts to deploy the EV charging infrastructure, if the U.S. is to meet its carbon goals. Private companies have the ability to deploy charging stations on their own. Policymakers should step in to educate and facilitate where possible.

Policymakers at the state, city or county level can also play a direct role in supporting EV adoption through clean car incentives. The largest financial incentives in the country are offered in California, Connecticut, New York and Massachusetts. But there are also EV incentives in oil country. Texas incentivizes state residents to purchase an EV with a rebate of up to $2,500, as long as the cars are purchased from a Texas dealership. Colorado currently offers the largest EV incentive outside the federal government. Electric-car buyers there can get a $5,000 tax credit for purchasing any electric “light-duty passenger vehicles” through 2020.

Part 2 will take a closer look at how utility regulation can support the development of EV charging infrastructure to the benefit of the entire grid system.