It’s been a tough few years — a tough decade, really — for big U.S. transmission projects seeking to carry wind and solar power from where it’s most cost-effectively generated to where it’s needed the most.

Major infrastructure projects are notoriously tough to build in 21st-century America, and that seems especially true for transmission lines, however critical they are in transforming the energy system.

The case for new multistate transmission lines has never been clearer. A growing number of states and utilities have set 100-percent-clean-energy goals, albeit with no obvious path to generating all that power close to home. The gap is growing between the transmission network’s capacity and the need to link wind farms in the Great Plains and Intermountain West, solar farms in the Southwest and hydropower resources in eastern Canada to other regions hungry for carbon-free energy.

Even within individual states, such as Texas, congestion costs, instances of negative grid pricing and other effects of the lack of sufficient transmission are rising, underscoring the need for new projects.

Transmission projects can be derailed at many points in their decade-long timeframes from conception to completion. Failure to gain regulatory approval from every state they cross, public opposition from environmental groups and communities worried about their negative impacts, or the refusal of any landowner along their path to cooperate are ever-present risks and have led to several high-profile project failures.

The tally of canceled projects includes Eversource's Northern Pass project in the Northeast as well as the transmission lines that were part of the first, larger version of American Electric Power's Wind Catcher project (a smaller version is now moving ahead without new transmission). Ambitious cross-country transmission developer Clean Line Energy closed its doors and canceled or sold off its multiple projects, despite backing from utilities and state and federal agencies.

All the same, transmission developers have not given up. A surprisingly large number of major projects are still moving ahead, each with the opportunity to unlock big amounts of renewable energy and bring it to where it's most acutely needed.

Transmission developers have long said that if only a few big renewable-linked projects could get built, the path would open to others once the benefits were made manifest. That theory was largely left untested in the 2010s. Here are seven still very-much-alive projects that could prove it out in the decade ahead.

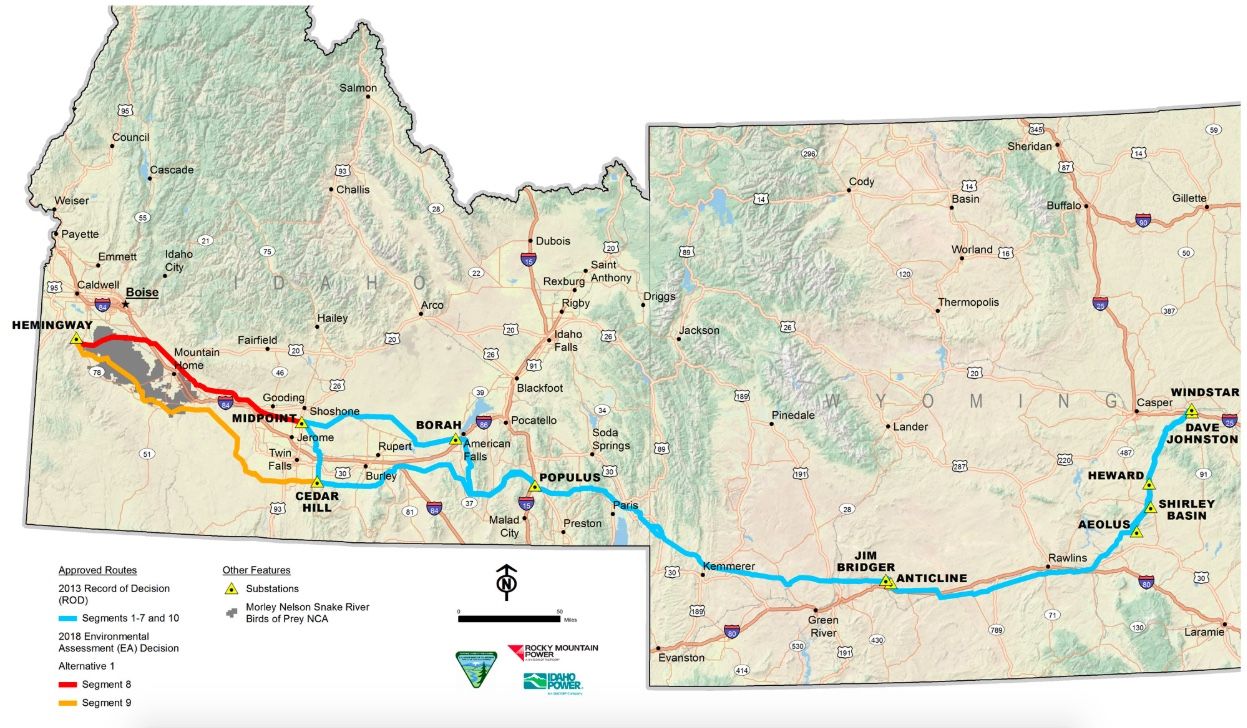

1. Gateway West

The 1,150-mile, $2.6 billion Gateway West project, first proposed in 2007, is one of several major transmission corridors designed to carry power from Wyoming’s burgeoning fleet of wind farms to populous West Coast markets. It’s also one of the few projects on this list that’s actively being built today, with hopes of completion by the end of 2020 — although the project still awaits state and local permits to reach the finish line.

Gateway West benefits from powerful backers with important local ties. It's a joint proposal of Idaho Power and PacifiCorp’s Rocky Mountain Power, which has big plans for growing its wind power portfolio in Wyoming as part of a broader long-range strategy to increase its share of clean energy.

This sweeping Energy Gateway Transmission Expansion plan includes Gateway West — expected to increase PacifiCorp’s wind power capacity by roughly 750 megawatts — as well as the Gateway South project, which would add another 1,500 megawatts of capacity running from southeastern Wyoming to northern Utah and is due to begin construction next year.

Gateway West's route from Wyoming through Idaho. (Credit: Rocky Mountain Power)

2. TransWest Express

First proposed way back when Gwen Stefani and 50 Cent were at the top of the pop charts, the TransWest Express Transmission Project is another one meant to carry wind power from Wyoming to faraway markets. The $3 billion project envisions a 730-mile corridor capable of carrying up to 3 gigawatts of power from southwestern Wyoming through Colorado and Utah to Nevada’s Hoover Dam, which connects to the clean-energy hungry grids of California and Arizona.

TransWest Express would link to the 3-gigawatt Chokecherry and Sierra Madre Wind Energy Project in southwestern Wyoming, among the largest wind projects ever proposed. Both the TransWest Express and the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre projects are owned by the Anschutz Corp., the private holding company of billionaire oilman Philip Anschutz.

In April 2019, TransWest won approval from the Wyoming Industrial Siting Council, the last of the state and federal approvals needed to move forward. This could allow the project to begin construction as early as next year and open for business as early as 2023, although individual landowners could still raise objections.

3. SunZia

The $1.5 billion SunZia Southwest Transmission Project faces an uncertain future, but its sheer size and profile secured its spot on this list.

SunZia is one of several big transmission lines geared to open renewables development in the Desert Southwest to help bring power to markets farther west. With a capacity of 3,000 megawatts, SunZia would be a critical link for the Pattern Energy's 2,200-megawatt Corona Wind development, a suite of projects approved by New Mexico regulators in 2018. The 520-mile SunZia project is owned by SouthWestern Power Group, a wholly owned subsidiary of MMR Group. Arizona utility Salt River Project owns a small share of the project, while former partners Shell WindEnergy Inc. and utility Tucson Electric Power no longer have ownership in the project.

But while Arizona regulators approved SunZia in 2016, New Mexico regulators denied the project’s permits in September 2018, putting its future in doubt. (In May, a spokesman for SouthWestern Power Group wrote in an email that the project has received other relevant federal and state permits, and will apply for its remaining permit in New Mexico "as time requires." The spokesman said the project is "very active and expects to place the first of two 500 kilovolt transmission facilities in commercial operation by 2024.")

If SunZia doesn't make it, several other big transmission projects in the Southwest could. Hunt Power's Southline Transmission Project would add 240 miles of new transmission lines from Las Cruces, New Mexico to southern Arizona, and upgrade another 120 miles of transmission connecting to Arizona utility Tucson Electric Power, boosting the line’s capacity to about 1,000 megawatts.

Then there's the Western Spirit Transmission line, purchased by Pattern Energy from the defunct Clean Line Energy Partners in 2018. The 800-megawatt line would link to the Mesa Canyons wind project and is being developed by Pattern in partnership with a state agency, the New Mexico Renewable Energy Transmission Authority.

Western Spirit has won federal and state approvals, and utility holding company PNM Resources has agreed to buy it for $285 million when it’s done. But the project is being opposed by two New Mexico counties and residents who say it will decrease property values.

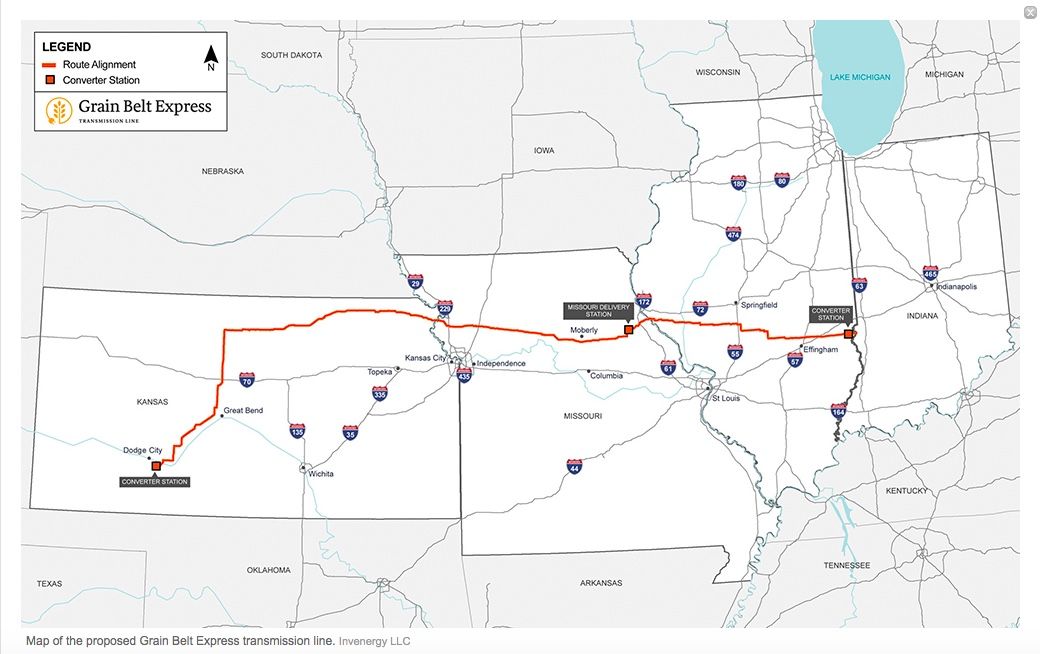

4. Grain Belt Express

The Grain Belt Express is another former Clean Line Express project, this one meant to carry up to 4,000 megawatts of wind power in western Kansas to its endpoint in Indiana, part of the 11-state system of grid operator PJM. But the 780-mile, $2.3 billion project has traveled a rough road due to its need to win over regulators and landowners in the four states it crosses.

After initially being denied by Missouri regulators, Grain Belt won a court battle to allow a rehearing in 2018, only to have another court in Illinois overturn that state's approval of the project weeks later — underscoring the whack-a-mole reality of multistate projects.

Invenergy, the Chicago-based renewables developer, bought the rights to Grain Belt from Clean Line after that company folded. Invenergy then won approval from Missouri regulators to be designated as a public utility, which would give it the power to use eminent domain to secure rights of way for the project.

But this galvanized opponents, including landowners and the Missouri Farm Bureau. After losing a court challenge, the landowners successfully lobbied the Missouri state legislature to introduce a bill that would bar Invenergy from using eminent domain, which is now being considered in the state’s senate.

The battle for the Grain Belt continues: Invenergy recently offered to open the right of way for use to deliver broadband internet service to rural Missouri communities in hopes of convincing state lawmakers to ease their opposition.

The Grain Belt Express would cross four states, bringing wind power from Kansas to the PJM market. (Credit: Invenergy)

5. SOO Green HVDC Link

The 349-mile SOO Green HVDC Link would harness wind resources across Iowa to northern Illinois, connecting wind-rich grid operator MISO to mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM. If that sounds familiar, SOO Green is designed to avoid the problems that have dogged the Grain Belt Express and other above-ground transmission lines, with a plan to bury its high-voltage direct-current cables underground and largely use existing rights of way owned by railroad companies.

This 2,100-megawatt line would be by far the longest underground HVDC transmission project in the country, compared to the 65-mile, 660-megawatt Neptune RTS undersea and underground cable connecting the Long Island Power Authority to New Jersey. It would also allow developer Direct Connect Development Co. to avoid opposition from landowners over what many consider unsightly overhead transmission cables and pylons, as well as dodging controversy over the possible need to use eminent domain to seize property from unwilling landowners.

Direct Connect, which is backed by investment from Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, Jingoli Power and Siemens Financial Services, hopes to start construction on the $2.5 billion project this year and finish by 2024.

6. New England Clean Energy Connect

A similar struggle between overhead and underground transmission lines is playing out in the Northeast. The overhead line in question is the proposed New England Clean Energy Connect project, which would carry up to 1,200 megawatts of Canadian hydropower from utility Hydro Québec south into Massachusetts to help meet the state’s clean energy goals.

In 2018, Avangrid subsidiary Central Maine Power won a bid to develop the $1 billion, 145-mile project — a replacement for the failed Northern Pass Transmission project. In January 2020, Maine’s Land Use Planning Commission approved the project. But opponents, who object to CMP’s plan to cut through 53 miles of forest, gathered enough signatures in March to place a referendum on this November's ballot.

Critics of NECEC note that there's another option: The New England Clean Power Link has approvals and permits to run an HVDC line about 150 miles from the Canadian border to a terminal in Vermont, partly under the waters of Lake Champlain and partly underground. But this 1,000-megawatt line being developed by TDI New England, which is owned by private equity firm Blackstone Group, is more expensive, at an estimated cost of $1.2 billion.

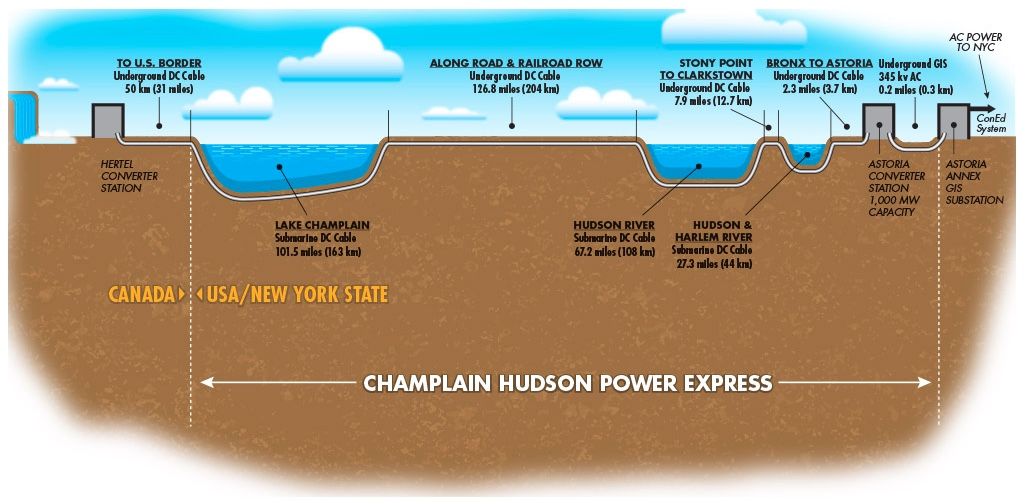

7. Champlain Hudson Power Express

TDI New England is also developing a longer 1,000-megawatt HVDC line, the Champlain Hudson Power Express, that would run 330 miles from the Canadian border to New York City, both underground along railroad and roadways and under the Hudson River. The $2.2 billion project is seeking New York state regulator approval for slight route changes, after having won approval for its original route in 2013.

But in an example of the multifaceted challenges facing these types of undertakings, environmental group Riverkeeper late last year reversed its 2013 support for the project, saying it would now oppose the transmission project. That’s because Riverkeeper opposes any more dam-building by Hydro Québec on environmental and social justice grounds; it fears that the utility’s 2018 commitment to supply power to New England could ultimately lead to the utility to build more dams in Canada to supply New York.