Energy storage has inspired a menagerie of metaphors to convey the versatility of its uses. Some call it the bacon of the grid, making other resources taste better. But the image of the Swiss Army knife captures the sheer number of different roles this technology can play.

In the coming weeks, Storage Plus will investigate each of the major tools, to understand their history, present and future. Instead of knife, tweezers and corkscrew, storage's tools include frequency regulation, capacity and many more. To kick things off, here's an account of the foundational market application for modern grid batteries: frequency regulation.

***

The modern U.S. energy storage market owes its present success to the role of frequency regulation, even if the industry has since superseded it.

Lithium-ion batteries made their first competitive entry into power markets when massive mid-Atlantic wholesale market PJM launched its fast frequency response market, also known as Reg-D, in 2012. That led to a flurry of investment, as legacy power producers, renewables developers and upstart newcomers built quickly to cash in on the rapid payback periods.

But, much like the momentary jolts of activity that make up frequency regulation itself, PJM’s market boomed briefly and then subsided. By 2016, new battery construction there had slowed. But battery developers, having proved they could actually make money on the technology, turned to other geographies and use cases.

For the first installment of the Swiss Army Knife of Storage series, we will examine the history of this pathbreaking application for battery storage and explore the limitations that caused it to recede from prominence. Of course, batteries still maintain grid frequency every day in various parts of the country, and some new markets beckon. A handful of developers are even seeking to resuscitate the long-dormant Reg-D market.

But for many companies, frequency regulation provided the diving board to launch them into a much deeper pool of energy storage opportunities.

A perfect fit

A decade ago, batteries weren’t cheap, but they were fast. Where heavy metal turbines took minutes to ramp up, batteries responded almost instantaneously. That made them a natural fit for ancillary services, the adjustments needed to keep the electric grid humming along.

Frequency regulation has typically been the best-compensated of the various ancillary services, which include spinning reserves, voltage support and more. But before storage could blossom in that role, it needed market rules that rewarded its speed.

The breakthrough came when the PJM wholesale market created the fast frequency regulation known as Reg-D.

"It’s something storage does much more cost-effectively than the next best alternative," said Ray Hohenstein, market applications director at battery integrator Fluence.

Battery construction in PJM took off in 2013 and reached its zenith in 2015. Legend tells of batteries earning two-year payback. PJM saw 100 megawatts of energy storage completed in the fourth quarter of 2015, a level of activity that the industry has rarely matched since.

Many of the biggest names in storage development today got their start chasing Reg-D.

Independent power producer AES dipped into storage in PJM, and it liked what it saw. The early projects there led to increasingly ambitious battery development, as well as the 2018 spinoff of its battery integration business into Fluence, a leading provider of large-scale storage systems.

Wind powerhouse Invenergy built two 31 MW plants in 2015 — Grand Ridge, in Illinois, and Beech Ridge, in West Virginia. That company went quiet on storage for several years but resurfaced as the winner of a massive contract with utility Arizona Public Service in 2019. NextEra Energy Resources launched its battery fleet with frequency regulation applications in PJM.

The end of an era

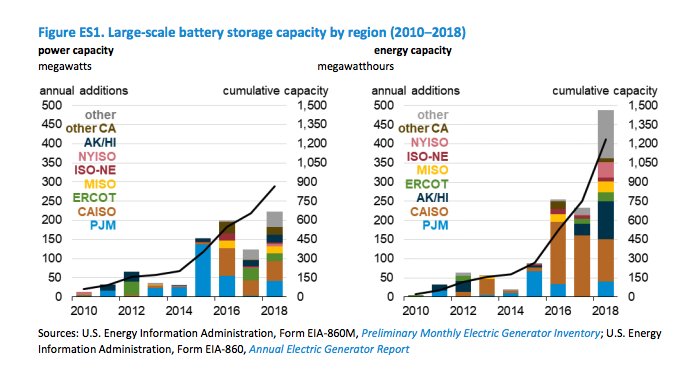

By the end of 2015, PJM absolutely dominated the total U.S. installed battery capacity.

But installations plummeted in 2016 and fell to almost zero in 2017 (as illustrated in the Energy Information Administration chart below). That year, a set of rule changes slashed the compensation that shorter-duration systems could earn. Many systems, built for 15- or 20-minute durations because they didn’t need to be longer, suddenly had to de-rate themselves, bidding in at lower nameplate capacity to meet a longer signal.

That rule shift didn’t have to happen, and it became emblematic of the risks of building a business case around newfangled rules that are subject to change. But other characteristics of the market spelled trouble for long-term growth.

A big one is the cap on how much frequency regulation a system actually needs, which usually limits the market to a few hundred megawatts.

“Frequency regulation is a small fraction of the total capacity market,” said Daniel Finn-Foley, energy storage director at research firm Wood Mackenzie “It’s not going to be a huge growth game-changer [for storage].”

An investment boom in a limited market was bound to lead to saturation. But the actual work of rapid charge and discharge takes a toll, too. Finn-Foley likened it to the physical impacts of playing football in the NFL.

“You have to get your turn pretty quickly, and the batteries are worn out after that,” he said.

Reg-D renaissance?

A few developers have tried to rerun the Reg-D play, with tactical adjustments for evolving market conditions.

Viridity teamed up with Dynapower to build two 20-megawatt/20-megawatt-hour systems in PJM in 2018. That hour-long duration was intended to boost the systems’ performance scores relative to the older competition.

“Reg-D is not dead, but you have to be smart about it,” Viridity’s then-CEO Mack Treece told GTM at the time.

A larger pair of projects followed that playbook in 2019: Energport integrated two 36-megawatt/36-megawatt-hour systems to chase Reg-D in PJM. The projects were supplied with lithium-iron-phosphate cells from Chinese manufacturer Sinexcel. The companies did not name the owner of the projects, but posted photos of the sites, in Illinois and West Virginia, that show Invenergy’s logo.

Those are in fact repowerings of Invenergy's original two PJM batteries, the developer confirmed to GTM Thursday.

"We had all the infrastructure there," said Kris Zadlo, who oversees Invenergy's storage business. "We did the analysis, and we decided it was worth the investment to replace."

The business case takes advantage of a new settlement between PJM and storage owners whose assets were affected by the early change to the signal. The settlement took effect July 1 this year and lasts for 42 months, locking in agreed-upon performance rules for Reg-D.

Invenergy ordered new batteries sized to fit on the same foundations and connect to the same hookups as the previous batteries, Zadlo noted. It took less than a month to install them. Now, the newly refurbished systems will have a leg up on the frequency regulation competition.

"As the battery degrades, your performance score degrades with it. Initially, a new battery will outperform older batteries on the performance score."

Compared to the frequency regulation heyday, though, these projects look like the exceptions to the rule.

“It’s rare that you’re going to see anyone build a single-service unit for fast frequency — those days are over,” said Jason Burwen, vice president of policy at the U.S. Energy Storage Association. “That’s not to say people aren’t going to use it as a revenue stream as part of their project finance.”

New horizons

Other developers are chasing different ancillary services in specific geographies, both in the U.S. and abroad in places like the U.K. and Australia.

"We still frequently see the first wave of energy storage systems in new markets capturing frequency regulation as a primary source of value," Fluence's Hohenstein said.

A big opportunity arrived in Texas when grid operator ERCOT approved a fast frequency response rule (FFR). Though it sounds similar to frequency regulation, this product is functionally quite different. To claim it, a battery must reserve capacity that it can deliver to the grid in case frequency decays past a certain threshold. FFR resources must respond with 15 cycles and deploy for up to 15 minutes.

"The units are only called upon intermittently, versus the 24/7 of regulation," Burwen explained.

A battery boom is underway in Texas, though it is not yet clear how many of those projects are chasing frequency response. Developer Broad Reach Power told GTM it is treating its batteries like an independent power producer’s generation fleet, selling energy products and hedges based on its capacity.

In Hawaii, developer Plus Power won a contract for the massive 185-megawatt/565-megawatt-hour Kapolei Energy Storage project. Besides shifting Oahu’s solar generation into the evenings, this battery will provide fast frequency response, taking over from the grid inertia provided by a nearby coal plant that will soon shut down.

As grids become increasingly renewables-heavy, sudden shifts in wind or sunlight can throw off grid frequency. That could lead to a growth opportunity for battery-based frequency response. Similarly, coal plant retirements proceed nationwide, leaving behind inertia needs that batteries can chase.

Those opportunities may not drive investment theses just yet, but they could soon.