For five years running, author Tam Hunt has provided his take on global clean energy markets in his Solar Singularity series. Read his first installment in this year's update here, covering solar and batteries.

***

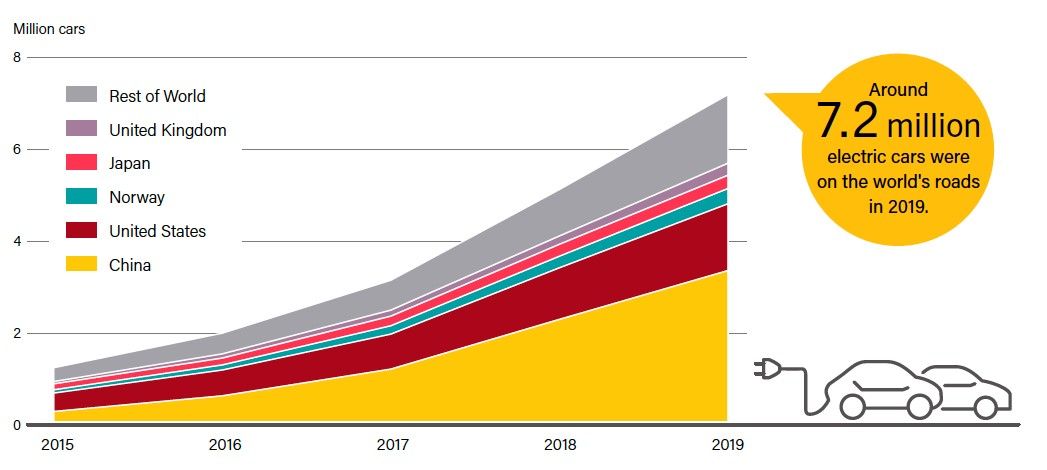

I was optimistic about EV growth in last year’s update and was growing more optimistic this year because of the breadth and depth of the global EV market. Numerous new EV models became available in 2019 and 2020, and global markets showed strong sales for 2019 and early 2020.

But some forecasts show EV sales slumping up to 43 percent in 2020 year-over-year, so 2020 is sure to be a serious blip in the overall growth story. We need to look past the current downturn to see the long-term growth story more clearly.

As with solar and wind energy, China has become the global leader in terms of both technology development and adoption of EVs and many other green energy technologies. The Chinese EV car market tripled in just the last two years, and China dominates the now-large global electric bus market. Other than Tesla, many of the global EV market leaders in terms of sales are Chinese.

Meanwhile, in Europe, we see a number of companies taking the lead in EV sales in various countries, including market EV sales leaders Norway and Germany.

Norway was the overall market leader again in terms of percent of EV sales, surpassing last year’s records easily with fully 70 percent of all new passenger car sales coming from the EV segment for the first four months of 2020. Unlike last year, this year’s EV sales in Norway include very few Teslas (2019’s early-year growth was driven primarily by Model 3 sales). The Audi e-Tron topped the list, with 4,586 vehicles sold. The VW e-Gold and Nissan Leaf rounded out the top three.

Twenty EV models saw more than 500 vehicles sold in Norway, showing that the plug-in market is now quite deep and not dependent on just a few companies. Norway continues to show how EV markets will probably unfold in other countries.

We are witnessing the “EV singularity” in some countries: the point at which EVs become so cheap and appealing for consumers that they become the default new vehicle type for most purchases.

Norway, with significant EV subsidies, seems to be the first nation to undergo the EV singularity. But Germany, a much larger economy, may not be far behind; it seems to be on track to hit a 10 percent plug-in vehicle market share by the end of 2020 (with most of these plug-in hybrids).

Globally, plug-in sales were up 10 percent in 2019, which is good but not great. The first half of the year was considerably stronger than 2018, but the second half dropped off, as lower subsidies in China ate into demand.

This slowdown in 2019, with no pandemic to excuse it, worries me about the ability of EV sales growth to continue. The counterargument looking forward is that there are now a number of increasingly affordable long-range EVs either on the market or coming to market, making EV options for “real cars” increasingly numerous.

Global plug-in EV sales, 2015-2019

Source: REN21

In the U.S., EV sales were not as good as hoped last year (and nowhere near Norway or Germany’s market share). 2018 was a breakout year but 2019 underwhelmed, with a 7 to 9 percent decline in overall sales, according to data from Edmunds and InsideEVs.

The pandemic is likely to leave 2020 as another year of negative growth for EV sales in the U.S. and globally. A recent BloombergNEF forecast concluded that battery shipments to carmakers will fall by 14 percent in 2020.

Some good news is that after a significant further slowdown in early 2020 due to the pandemic, China’s EV sales shot back up in May, with China now Tesla’s largest market (over 11,000 Model 3s sold in China in May alone, tripling April's numbers).

This news has helped put a rocket beneath Tesla’s stock price and made it the world’s most valuable auto company despite having a fraction of the sales of other high-valued manufacturers. (Full disclosure: I own a few shares of Tesla and Google.)

Lyft made waves by announcing this June that it had committed to a fully electric vehicle fleet by 2030. It is likely that other rideshare companies will follow suit. And as the world shifts to a “transportation-as-a-service” model, it becomes increasingly important that companies like Lyft, Uber, Didi Chuxing, et al. are mostly or fully electrified.

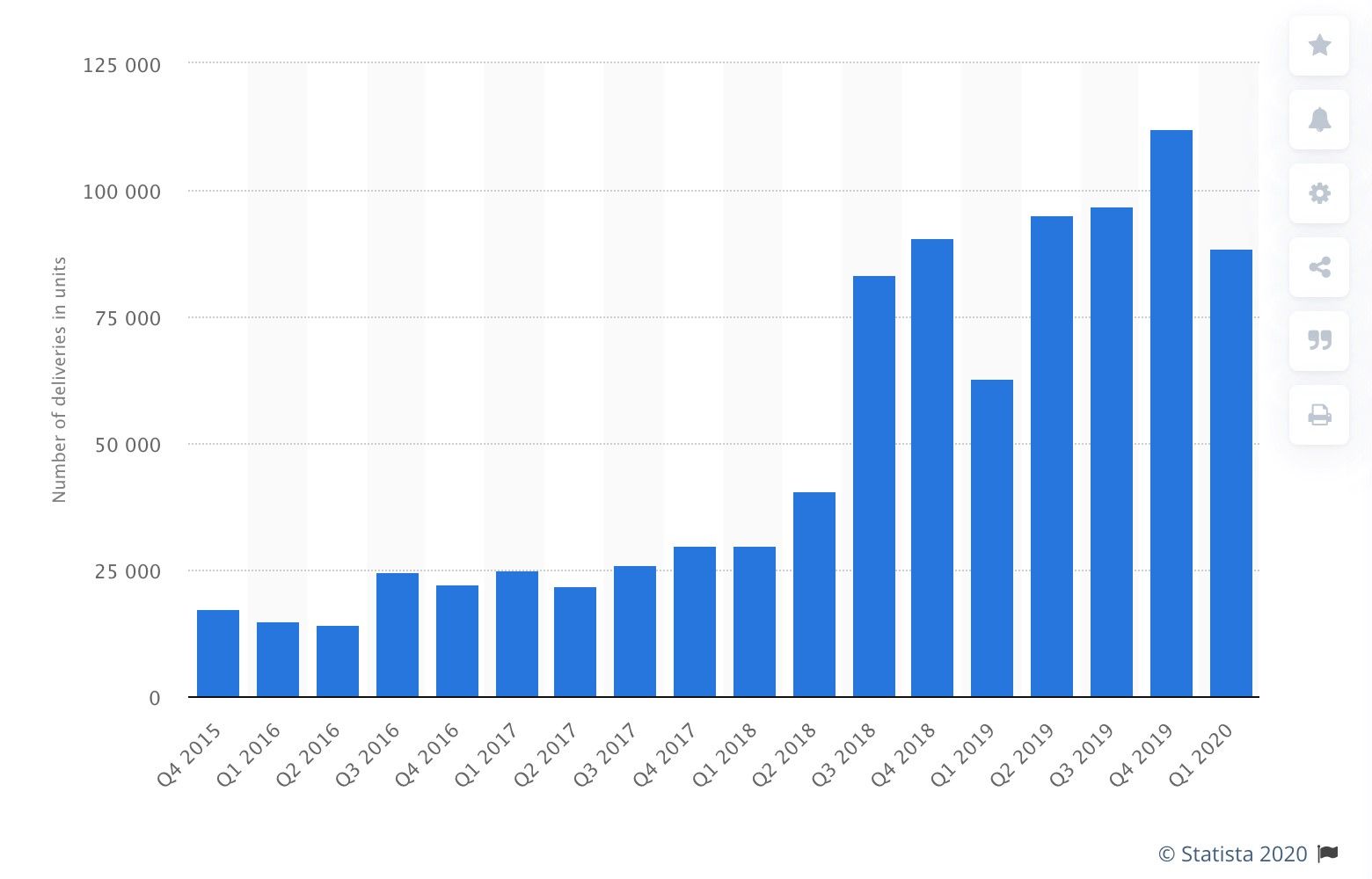

Tesla continues to lead the plug-in market globally. Its Model 3 dominated 2019 global sales, with over 300,000 sold, more than doubling the next-best seller (the BAIC EU series, with 111,000 sold). The start of Tesla’s Model Y deliveries was the big news for 2020, almost overshadowed by the bizarre but increasingly popular Cybertruck (yes, I ordered one too). Both of these vehicles will likely be significantly more popular than the Model 3, setting Tesla up for continued domination of the global EV market and strong growth moving forward.

Tesla sold 393,000 vehicles in the last four quarters, up from 278,000 in the prior year (Q2 2018 to Q1 2019), for a growth rate of about 31 percent. It passed the iconic milestone of 1 million vehicles sold in May 2020.

A 31 percent vehicle sales growth rate leads to doublings approximately every 2.25 years, which would, if it continues, result in Tesla sales of almost 800,000 in the 2022 or 2023 timeframe, and over 2 million annually by 2025 or so. Past growth is not destiny, so I am not presenting a forecast here.

We are in strange times, and it’s impossible to forecast the next few years with any certainty. That said, the arrival of the Model Y — Tesla’s first offering in the extremely popular crossover SUV niche — and the pending arrival of the Cybertruck suggest that Tesla’s sales curve will continue to rise rather than shrink.

Tesla's quarterly vehicle deliveries, 2015-2020

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

Tesla’s average revenue growth has been very strong, but it fell substantially in 2019 and may be relatively low for 2020 also. The average annual gross revenue growth has, however, been 99 percent since 2011, even with 2019’s decline, which is truly remarkable by any standard.

Battery storage costs for EVs continue to fall, dropping to $156/kWh in 2019, 87 percent lower than in 2010 ($1,100/kWh), according to BloombergNEF’s recent report. The learning curve for battery storage, which I call the “Kammen curve,” has demonstrated an average 17.3 percent decline in the cost of energy storage with every doubling of global production. This kind of reliable cost decline over time allows some confidence in predicting continued robust growth rates.

BloombergNEF predicts that prices will fall below $100/kWh by around 2024, at which point EVs will start to reach upfront price parity with internal combustion vehicles. This will result in the “EV singularity” mentioned above.

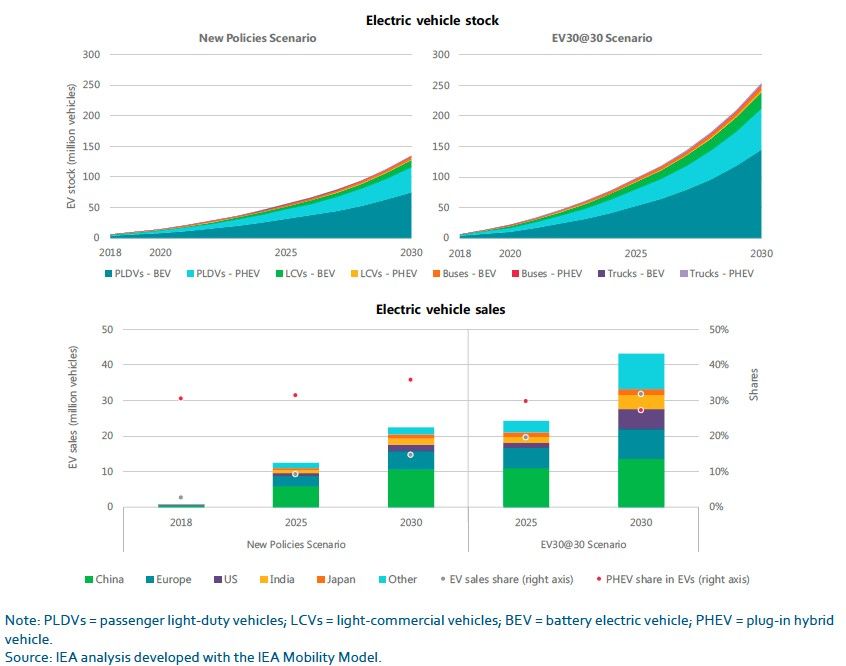

Light-duty EV sales have been good, but far from stellar, over the last two years. Sales will probably rise at a faster pace in the coming few years as more models become available, prices continue to decline and more people start to recognize the advantages of EVs compared to “normal” cars.

It’s still relatively early days for EV growth so it’s hard to say where adoption will be by 2030, but as with most of the intertwined green energy revolution technologies, most forecasts are steadily increasing as adoption increases in the present timeframe.

Forecasters are paid to provide educated guesses, but as the public becomes more comfortable with new technologies and early technology offerings become more sophisticated, professional forecasters become more comfortable offering more dramatic adoption forecasts. That’s what we’re starting to see across the board for green energy technologies.

The International Energy Agency’s global EV Outlook, released in June of this year, shows further development of encouraging recent trends. Under existing and announced policies, the IEA forecasts 23 million EVs on the road by 2030 (up from about 8 million in 2020). Under a more aggressive scenario, which adds pledges by many countries to existing policies, that number increases to 43 million and fully 40 percent of the new light-duty vehicle market.

That’s great but not as fast as we need to be growing if we want to see the fleet turn over fully to EVs by 2040 or sooner (vehicles last for 15 years or so, so we’ll need about 15 years after all new purchases are EVs, each year, to reach a near-100-percent EV fleet).

Source: IEA

Full self-driving comes to a city near you

The last major trend I’ll look at is self-driving cars. This is a key part of the green energy revolution because of the vast increase in vehicle efficiency that can occur with a computer driving a car, and with cars becoming a service rather than a purchase. Studies have found up to 90 percent or more fuel savings are possible with a fleet that is autonomous and offered as a service rather than cars being owned. That’s clearly a serious game-changer.

Given the social-distancing rules now being practiced around the world, it’s possible that demand for robotaxis and robo-delivery may grow very rapidly once kinks are worked out, because of fears about public transit and carpooling, among other concerns. These trends will hit public transit very hard (a very unfortunate trend) but may serve to accelerate robotaxis and related technologies.

Google’s Waymo appears to remain king of the hill for full self-driving (FSD). Its pilot robotaxi program in Phoenix, with no safety driver in the car (so these cars are truly autonomous, but operate in a limited area), went public in 2019 and is expanding to the Bay Area in 2020. Waymo achieved a milestone of over 100,000 fully robotic rides in Phoenix by December last year. These systems are “geofenced,” however, so expanding them to full geographic coverage may take many years under the approach Waymo is currently pursuing.

Waymo is also developing robot delivery options with Waymo Via. Waymo raised $2.25 billion earlier this year from outside investors, a strong vote of confidence for the company's potentially world-changing technologies.

AutoX, a Chinese company, began its own robotaxi service in Shanghai in April 2020. This service went live in China after the country's coronavirus pandemic had mostly subsided; the hailing and interaction processes can be completely touchless. AutoX received a robotaxi permit for California in June 2019 and is operating a pilot program in the state, with a human safety driver still required. AutoX’s California pilot is known as xTaxi and is headquartered in San Jose.

MobilEye, now a unit of Intel, recently announced plans to roll out robotaxis with no safety drivers in 2022, starting in the company's hometown of Jerusalem.

China’s equivalent to Uber, Didi Chuxing, is also planning a robotaxi service in Beijing and Shanghai, as well as California, receiving major new investments in 2020. It recently began a robotaxi service in Shanghai, but with safety drivers for now. The company is targeting 1 million robotaxis on the road by 2030. Baidu, another Chinese internet giant, is also developing a robotaxi service and is offering rides already, but again with a safety driver in the car.

At least one analyst believes that Tesla is pulling “away from the pack” on autonomous driving development. Tesla’s latest update to its Navigate on Autopilot feature is pretty exciting because it allows self-driving in all-weather conditions and can handle stoplights and stop signs. In other words, Teslas equipped with the Full Self-Driving option (a higher cost option than the Autopilot option) can now in theory handle almost all driving with no inputs from the driver.

Tesla will, according to some reports, be offering autopilot lane changing on city streets, known officially as “Autosteer on city streets,” in a few months. This will complete Tesla’s long-planned Full Self-Driving package. When this happens, along with existing stoplights and stop sign functionality, true driverless driving will in many circumstances be here. This was supposed to have arrived by the end of 2019, but if it happens by the end of 2020, it will still be a remarkable achievement.

Tesla is taking a very different path than that of Waymo. The latter relies primarily on high-definition mapping as well as algorithms, whereas Tesla relies on computer vision without maps being involved at all. Tesla believes its approach, while more difficult at the outset, is a more scalable solution and will allow true FSD sooner than will other approaches. Waymo’s method is partly why Waymo is still limited to geofenced areas.

Waymo, TuSimple (another Chinese company), and a number of other companies are making progress on self-driving trucking, with Waymo expanding existing pilots throughout the U.S. Southwest and Texas in 2020.

These companies’ continued progress on FSD seems to contradict the growing chorus of naysayers who are pessimistic about the possibility of FSD (without safety drivers). It’s strange to me that we still have many critics of FSD saying we are still many years away from having working robotaxis on the road. Yes, Waymo’s robotaxis are still geo-fenced, but they already function properly in almost all weather conditions, and their fencing is gradually expanding in each area and to new areas. And Tesla’s progress on non-geofenced applications is impressive, albeit slower than expected. It’s not at all hard to see how these trends could lead to Level 4 or even Level 5 self-driving being available everywhere and in all conditions in the next few years.

I’ll make no predictions about when L5 FSD will be widespread (though I have made some personal bets with friends); there are too many uncertainties and black boxes involved. We know, however, from abundant data over the last two decades, that it’s not smart to bet against Elon Musk. Yes, he’s often delayed, even by years sometimes, but the man just gets things done. FSD is likely to be another of those technologies he just gets done. We’ll see before long if this is true.

Summing up

While there are many very substantial positive developments in the various technological revolutions making up the strands of the braid that is the “solar singularity,” I have to acknowledge that there are risks to continued progress, particularly on the EV sales front. It’s a weird time. And a lot could still go wrong with the global pandemic.

The most likely outcome of the pandemic and global recession seems to be some serious but temporary setbacks for green technologies, but overall we’ll see things get back on track, hopefully later this year or early next. And the long-term trends remain highly positive for the green energy transition.