Solar and wind are becoming the default option in power markets around the world.

That’s helping to moderate or lower emissions in electricity, but that sector makes up just a fraction of the global economy. While electricity and heat production account for about a quarter of global emissions, trucking, cement, steel, plastics, shipping and aviation currently account for 30 percent. And as the power sector gets cleaner, that share could spike to as much as 60 percent.

Fighting climate change requires sweeping changes everywhere, across all sectors.

According to the International Energy Agency, electricity generation from renewables reached 24 percent in 2017 and will climb to 30 percent by 2022. But the challenge to go carbon-free gets even steeper when it comes to the “harder-to-abate” sectors, like heavy-duty transportation and industrial processes like cement and steel production.

As Tom Heggarty, a senior solar analyst with Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables, said, “We’ve kind of got it easy in the power sector.”

A new report from the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC), a diverse coalition that includes Royal Dutch Shell and the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), however, argues achieving net zero carbon emissions in these sectors is technologically and economically possible by 2060.

According to ETC Co-Chair Lord Adair Turner, “There’s no doubt that it’s technologically doable — but it is challenging.”

Much of the challenge lies in converting large portions of the industrial process to use heat from electricity rather than fossil fuels. Huge swaths of global transportation infrastructure will also have to be electrified. And to make sure that electrification is truly carbon-free will require a great deal of solar and wind capacity.

Heavy industry and transport have often been viewed as secondary priorities for electrification. But the commission’s conclusion comes not long after a jarring report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that indicated the planet is on the precipice of a global crisis.

To keep warming below 2° C, and avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change, the commission said it’s essential to target rapid decarbonization across all sectors.

“We are facing a planetary emergency, and we need to decarbonize the global economy as fast as possible,” said Jules Kortenhorst, CEO at Rocky Mountain Institute and an ETC commissioner. “There is no more excuse to not pursue progress along all of the axes, all of the levers of decarbonization.”

“Clean energy is almost everything” when the world electrifies everything

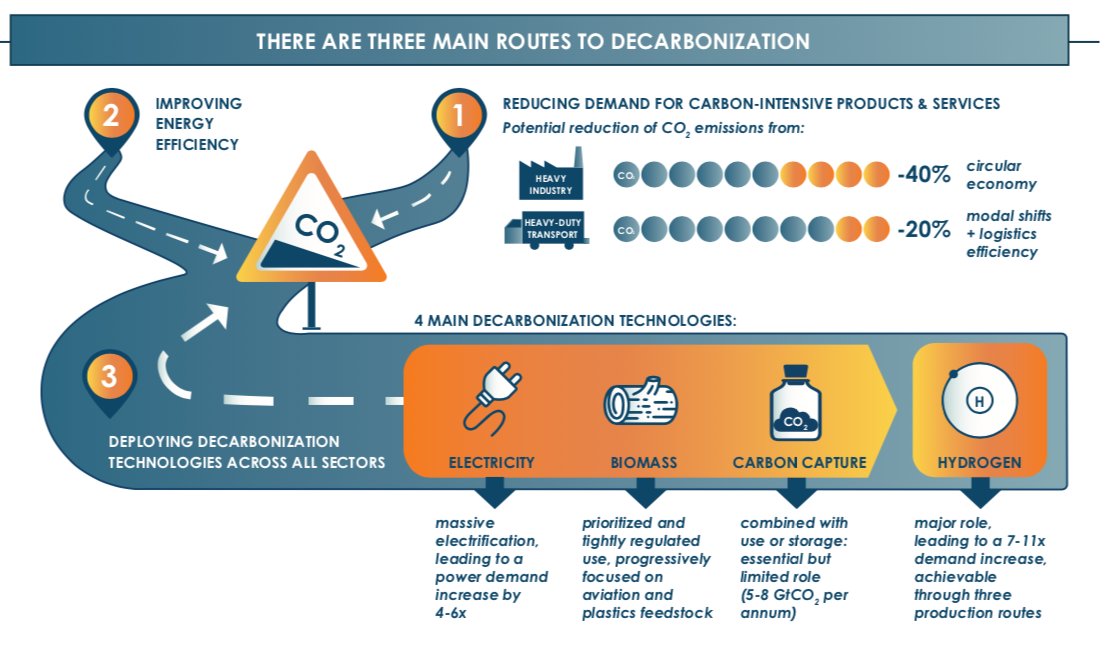

Turner notes that, overall, there are generally two ways to decarbonize harder-to-abate sectors. First comes reducing demand and increasing efficiency: cutting down on product use through recycling and reuse that creates a more circular economy.

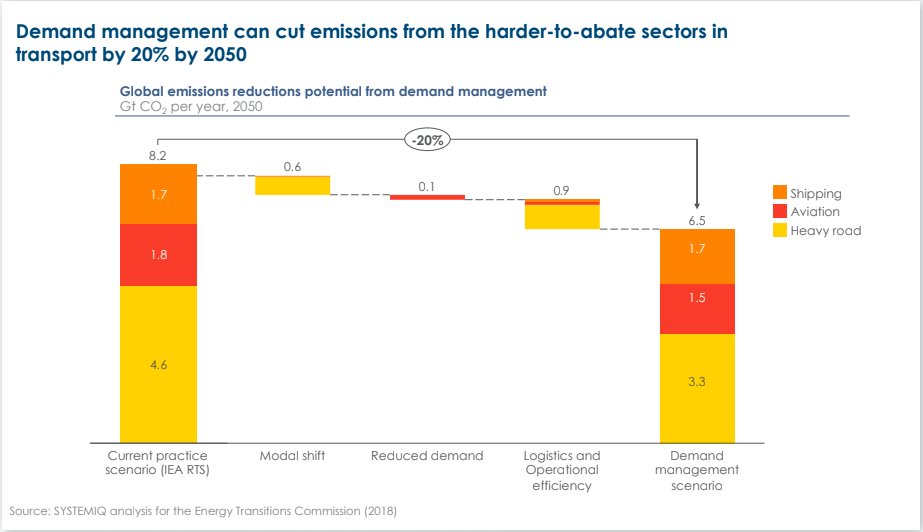

The ETC points to reuse of steel and aluminum products and car-sharing as a way to drive down the need for those metals, for instance. Using transportation as an example, demand management and logistics efficiency can reduce global emissions in aviation, shipping and heavy road use by 20 percent, from over 8 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year by 2050 to 6.5 gigatons per year.

Source: The Energy Transitions Commission

In industry, those same philosophies of limiting demand and increasing efficiencies can cut global emissions from steel, aluminum, plastics and cement by 40 percent. In developed economies the potential is even greater, with cuts of up to 56 percent by mid-century.

Those efforts can only go so far, though.

“Once you’ve exhausted those possibilities to constrain demand,” that’s where electrification comes in, according to Turner. While it's just one of the decarbonization techniques the commission presented, Turner said electrification will need to play the most central role in reducing emissions from the harder-to-abate sectors.

“Both in the industry sector and in the transport sector, electricity can become a much larger part of the solution,” said RMI's Kortenhorst. “Of course, if you want to do that, you have to make sure that it is clean electricity...from wind and solar and geothermal and hydro, and not electricity made from coal-fired power generation.”

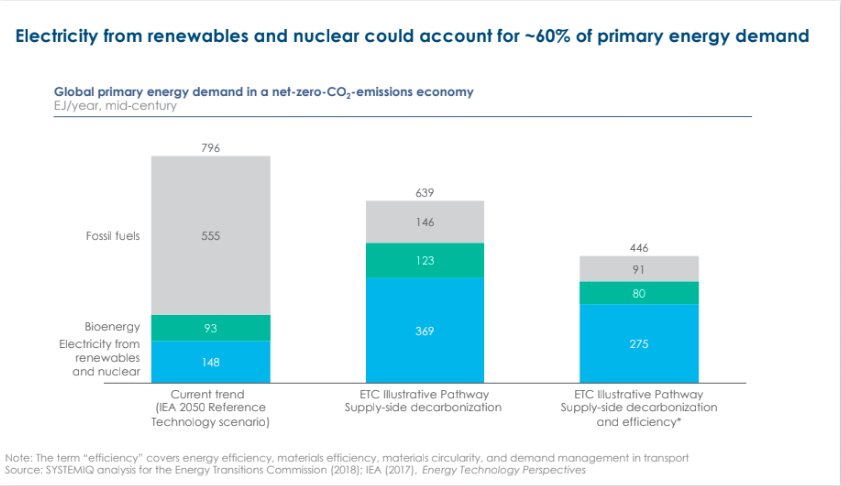

By mid-century, electricity should account for 60 to 65 percent of final energy demand, according to ETC’s analysis. Long-distance transit, like shipping and air travel, will likely continue to rely on some form of liquid fuel looking ahead. But industrial processes like steel production could begin to use electricity as a high heat source, either directly or through the production of hydrogen.

Gains in efficiency and demand management will also reduce overall electricity use. But further decarbonization will come from a sizable increase in renewable electricity. By 2050, ETC recommends that zero-carbon sources like wind, solar and nuclear produce 85 to 90 percent of the electricity mix.

“Clean energy doesn’t [just] fit in; clean energy is almost everything,” said Turner. “The renewables bit is the biggest single bit.”

Biofuels or fossil fuels using carbon capture and sequestration will make up the remaining portion, at just 10 to 15 percent of the total mix.

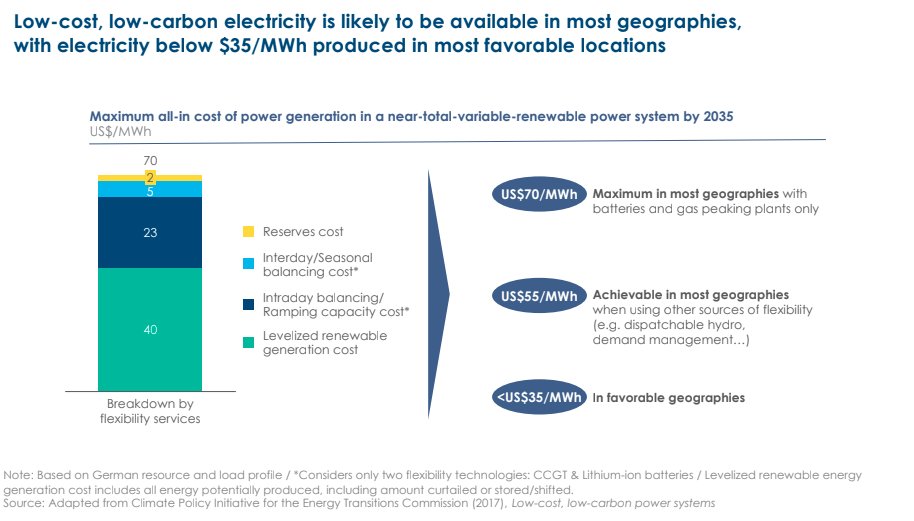

The already-dramatic cost reductions in wind, solar and storage help make such high penetrations of renewables possible, according to Turner. WoodMac research published this summer, for example, showed global solar capacity prices dropping from $1.50 per watt in 2015 to a forecasted $0.67 per watt by the end of 2023.

By mid-century, the commission projects electricity prices will be at a maximum of $70 per megawatt-hour and less than $35 per megawatt-hour in areas where solar and wind power are cheapest.

In addition to decarbonization through electrification and reducing demand, ETC notes that improving energy efficiency must also contribute to reducing global emissions. Increasing efficiency in logistics, trucking and industrial production could reduce energy consumption 15 to 20 percent.

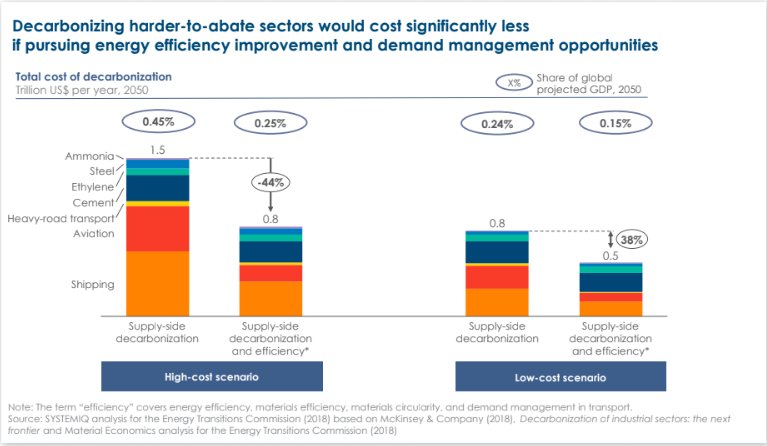

Using a combination of demand management and efficiency in energy and materials, in addition to electrification and renewables, also means significant cost savings for a decarbonization scenario.

With no demand and efficiency initiatives, costs top $1.5 trillion per year. Using those two levers drops the price tag 44 percent, to $800 billion.

That number isn’t small. But most of the abatement costs are on the supply side.

Source: The Energy Transitions Commission

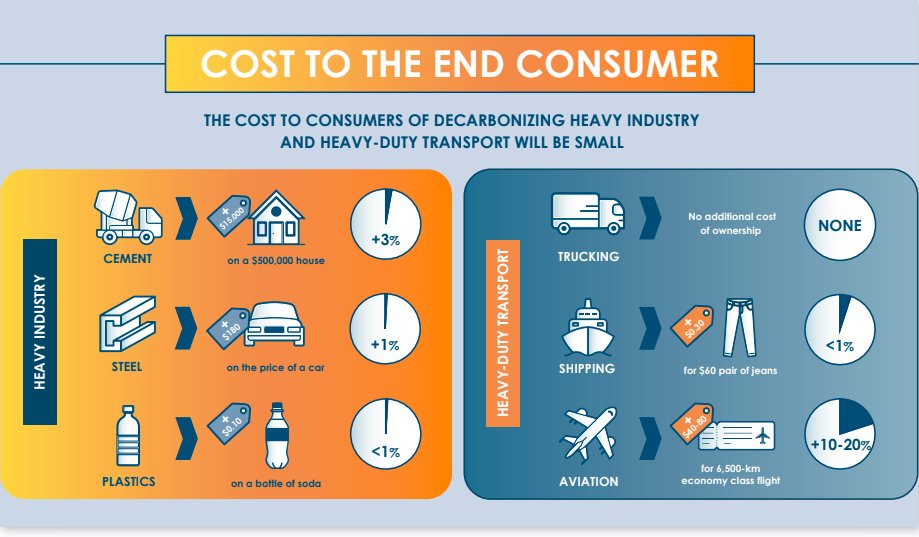

The ETC said there’d be little added cost for consumers, totaling about $180 on the sale price of a car or less than 1 cent added to a bottled drink.

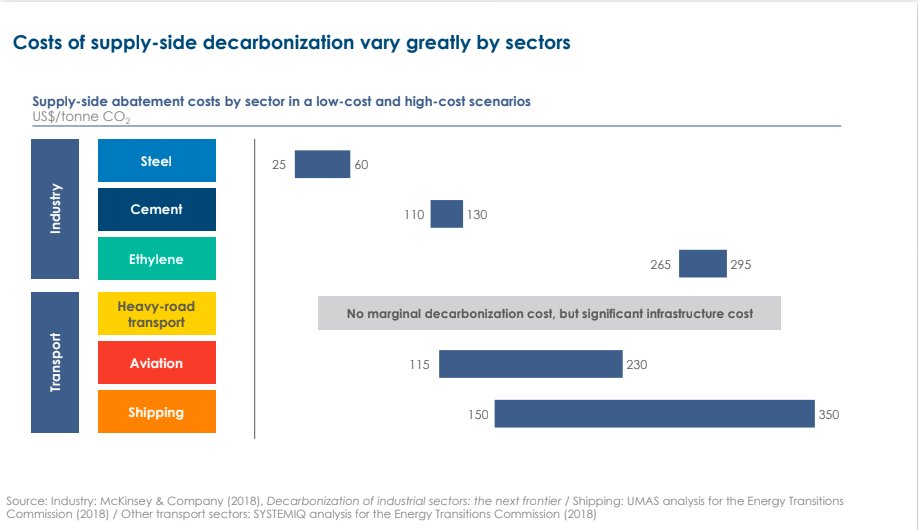

Intermediate products, like steel, face the biggest economic challenges. The ETC said zero-carbon steel could cost 20 percent more per ton than conventionally produced steel. But overall, the commission forecasts that economic impacts will be slight. Taken as a portion of global gross domestic product, the ETC said the costs don’t even reach 0.5 percent of the global total.

The most expensive industries to decarbonize, like aviation and shipping, rely on heavy fuels to travel long distances. Those can’t easily be electrified. In those sectors, some type of liquid fuel will likely still play a role. Electric batteries or hydrogen storage may be applicable for shorter distances.

“We have all the technologies we need”

Even though electrifying industries like shipping will be challenging, Kortenhorst points out that not even the most difficult areas require a “complete breakthrough” in technology.

Both Kortenhorst and Turner said decarbonization relies more on improving and scaling existing technologies than developing completely revolutionary ones.

“It’s not as though we’re looking for the next steam engine or the next LED lightbulb,” said Kortenhorst. “It is clear that when it comes to the electricity system, when it comes to passenger mobility, when it comes to energy efficiency — we have all the technologies we need. They are becoming cost-effective at a pace that very few people could imagine and there is no more excuse about focusing on the full and immediate decarbonization of [the transportation and industrial] sectors as quickly as possible.”

Kortenhorst also said the commission’s findings differ from many past climate reports that include industry stakeholders because the role of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) is relatively small.

Though fossil fuel companies such as Shell and British Petroleum sit on the commission, Kortenhorst said the amount of CCS in its decarbonization scenario doesn’t “defy sense of realism.” Instead of envisioning a future where CCS scales significantly from its current development, commissioners relied on technologies already on their way to maturity like wind and solar.

Where more of a push is needed, the commission said, is on the policy front.

“We won’t get there unless there’s forceful policies to take us from A to B,” said Turner.

So far, cohesive global policies on climate have been somewhat elusive. The Paris agreement, which every country but the U.S. has pledged to follow (though the country is still signed on), set out a process to work toward a target of well below 2° C. But the pact didn’t actually set out a concrete path to get there. Instead, it relies on promises that each country will continue to ratchet up their ambitions.

And even if the world’s economies all decided to suddenly move toward zero-carbon industries today, that could be detrimental in economies where electricity is still reliant on coal-fired power. Kortenhorst said transitioning too early remains a risk because some countries are still reliant on thermal fuels.

Turner said the pace of the transition ranks among the top decarbonization challenges. It’s also a risk to move too slowly, because the situation is so severe. In its report, the IPCC laid out a timeline of just 12 years to avert the worst impacts of climate change.

Both Turner and Kortenhorst mentioned carbon pricing as a powerful tool to push economies toward less carbon. The report recommends prices between $150 and $300 per ton of carbon dioxide for shipping and between $25 and $60 per ton of carbon dioxide for steel.

The report also called for policies that support infrastructure for renewables and electric vehicles and for public investment in innovation and commercialization of existing technologies. The commission said policymakers will also have to continue pushing on CCS and hydrogen-related technologies. According to ETC, demand for hydrogen could balloon sevenfold to elevenfold because hydrogen can fill in as a heat source or reduction agent where electricity cannot.

The commission didn’t provide concrete answers on how to create consensus on climate and decarbonization goals. But agreement around the report's central thesis from a wide variety of actors, including Engie, the World Resources Institute and banks like HSBC, shows a growing recognition even among some oil and gas companies that the market for fossil fuels is limited.

“As an organization deeply committed to the acceleration of the energy transition to ensure a world...in line with the Paris Agreement [target] of well below 2 degrees, [RMI has] found the discussions in the Energy Transition Commission constructive and truly focused on that Paris goal,” said Kortenhorst. “There was absolutely no hiding from that top goal.”

Still, the path set out by the commission remains just one part of ambitious climate action. The IPCC’s grave report suggested that carbon dioxide emissions must drop to zero by around 2050 to keep warming below or close to 1.5°C.

Kortenhorst said the ETC report sets “an important action agenda” for the future. Looking into the next year, the commission plans to continue pushing for implementation of its findings. Part of that will mean incorporating even more voices and building membership, especially among U.S. companies. Most of the group’s energy heavyweight members are based in Europe.