California utility PG&E wants to prove that massive batteries can replace gas peaker plants and save ratepayers money.

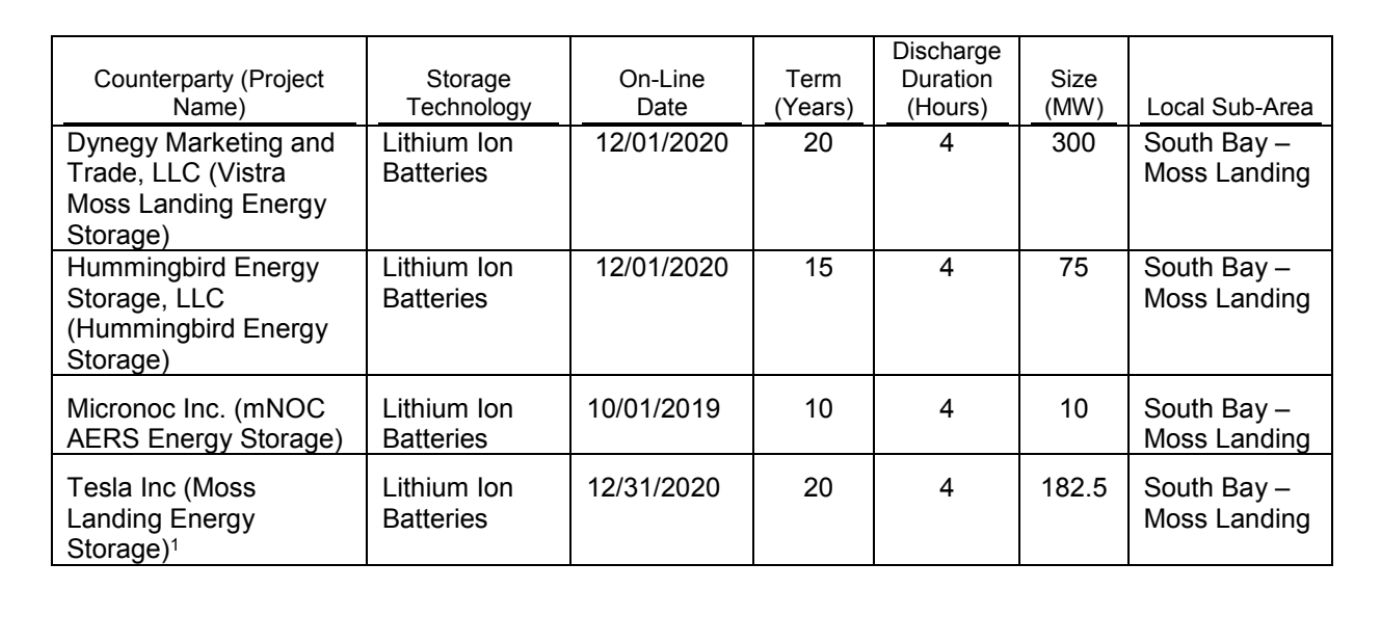

The company asked regulators to approve four energy storage plants to provide local capacity for the South Bay/Moss Landing sub-area. The request includes two of the largest battery systems ever proposed: a 300-megawatt/1,200-megawatt-hour project by Vistra Energy and a 182.5-megawatt/730-megawatt-hour project from Tesla.

Besides breaking the record for storage capacity — currently held by Tesla’s 100-megawatt system in Australia — this procurement will test a pivotal question in California’s effort to decarbonize the electric grid.

The saga began when gas generator Calpine sought “reliability must run” status for three of its plants, which would guarantee compensation in recognition of the facilities’ role in serving grid reliability.

In an unprecedented move, the California Public Utilities Commission overruled the request in January and told PG&E to seek out storage alternatives. The CPUC’s analysis concluded that buying new batteries would be a better deal for ratepayers than maintaining the existing, economically challenged gas plants.

That suggestion was hailed both as a harbinger of the high-tech, low-carbon future and a reckless gamble with grid reliability.

Whereas gas plants can run as long as the gas keeps flowing, batteries run out of charge.

"If we get a 110-degree day in August 2019 and there are rolling blackouts because the batteries ran out of juice after 4 hours and we needed them for another 8 hours, maybe the PUC would rethink getting rid of gas-fired generators," said Wade Schauer, research director at Wood Mackenzie's Americas Power & Renewables team, at the time. "Until then, that seems to be the objective the state legislature and the PUC are after."

PG&E's answer to such concerns seems to be to build bigger than we've ever seen before.

The Vistra plant would be triple the size of the largest battery currently planned in the U.S., Fluence's Alamitos project. This would come online in December 2020 and operate for 20 years. The Tesla project would come online that same month and also operate for 20 years.

A 10-megawatt/ 0-megawatt-hour system from Micronoc Inc. would begin operations in October 2019 for a 10-year term, and Hummingbird Energy Storage would build a 75-megawatt/300-megawatt-hour system for a 15-year contract starting December 2020.

Hummingbird is a subsidiary of a newly formed company, and Micronoc has delivered a few megawatts of storage "primarily in South Korea." Vistra got into utility-scale storage with a 10-megawatt/42-megawatt-hour system at a Texas solar plant.

The filing from PG&E sheds some light on how the batteries can keep their costs down relative to existing or new gas plants.

Scale helps with component costs. The Tesla system will sit on PG&E land within the existing Moss Landing substation. Besides providing the utility with local capacity, "the Moss Landing Project will participate in the CAISO markets, providing energy, ancillary services, and other services to the CAISO-controlled grid."

Vistra echoed these factors in a note to investors. It will lower development costs by using existing interconnection from the mothballed Moss Landing units 6 and 7, and siting the batteries in an existing turbine building.

Anchored by the 20-year resource adequacy contract with PG&E ("an investment-grade offtaker," assuming that wildfire liability doesn't bring about bankruptcy), Vistra can use the system to provide energy or ancillary services in the wholesale markets.

By building big, the developers can ensure steady income from the PG&E contract and still have capacity left over to make money in the wholesale markets. Wholesale revenue introduces risks compared to designing project economics solely around a utility contract, but it can allow developers to bid more aggressively in the solicitation if they're comfortable with the risk.