In his State of the State speech last week, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker gave renewables advocates something to rally behind.

This spring, the governor said, Illinois must focus on “the pressing issue of adopting new clean energy legislation that reduces carbon pollution, promotes renewable energy and accelerates electrification of our transportation sector.” It’s a priority that helped Pritzker skate to the governorship in 2018.

Years before that election, Illinois laid out a path forward for renewables growth, when legislators passed the Future Energy Jobs Act in 2016. When the law went into effect in 2017, it required 4.3 gigawatts of new solar and wind by 2030, cleaned up the mechanism that collects money to develop renewables and created the state’s first community solar program.

Since 2016, the Illinois Solar Energy Association’s membership has quadrupled. Non-residential installations were slated to jump from about 16 megawatts in 2018 to 49 megawatts in 2019, before an even bigger climb to 144.7 megawatts this year, according to data from Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables. Utility-scale installations, barely topping 3 megawatts in 2019, were expected to rise to 44 megawatts in 2020 before shooting to 163 megawatts in 2021.

Despite the success, Pritzker’s assurance couldn’t come soon enough for developers and solar advocates. Though the Future Energy Jobs Act has fostered growth, its funding is all but dried up for some segments of the industry. Without more money to fund renewable energy credits, those markets — especially community solar — could skid to a stop.

“The renewable energy industry, which has been enjoying considerable growth, is due for a stall,” said Lesley McCain, executive director at the Illinois Solar Energy Association.

Cycles of boom and bust have become a common theme in state-sponsored solar markets. Periods of growth spurred by significant incentives, market-building legislation and helpful policy often give way to lulls or even crashes. For a state that’s inched past 20 others in WoodMac’s solar rankings since 2017, current circumstances mean Illinois could stumble before it emerges as a full-grown market.

Constrained growth may also keep the state from reaching its 25 percent by 2025 renewable portfolio standard target. And Illinois is already eyeing a higher renewables contribution: Pritzker campaigned on a target of 100 percent renewable energy by midcentury.

More than half of Illinois’s electricity came from nuclear in 2018, according to the Energy Information Administration, with coal accounting for 32 percent and natural gas for 9 percent. That leaves just a sliver for renewables, even as the state mulls kicking that percentage up to 100.

In search of a "Path to 100"

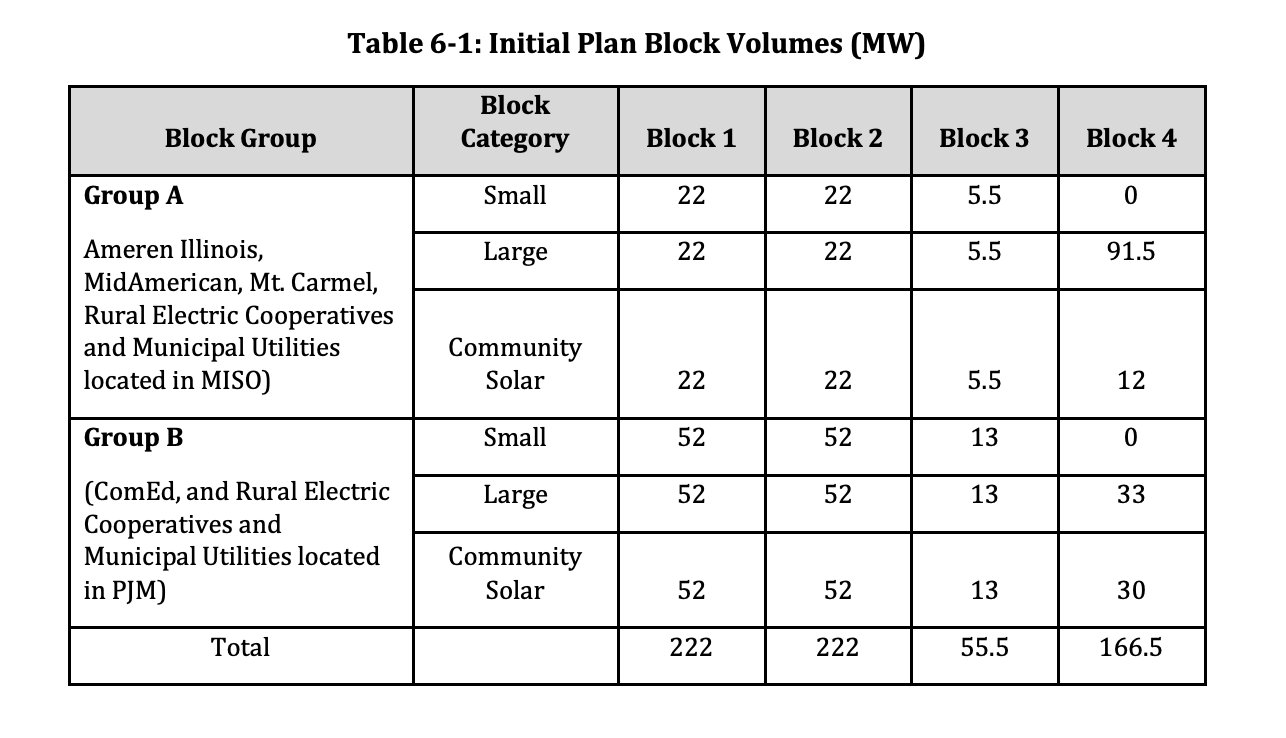

Much of the concern about Illinois’ program centers around distributed generation. The state’s “adjustable block program,” created by the 2016 law and administered by the Illinois Power Agency, was designed to spur about 666 megawatts of solar, equal to 1 million renewable energy credits.

The program lays out renewable energy credit prices for “blocks” of generation capacity that include community solar, small-scale solar (under 10 kilowatts) and large distributed projects (between 10 and 2,000 kilowatts).

Source: Illinois Power Agency

Developers have already chewed through all available capacity for the community solar blocks, but they're still working through the first of three blocks for small-scale solar, which includes residential. Large-scale distributed generation, which encompasses many commercial projects, still has nearly 24 megawatts of capacity open.

“There isn’t an overall freeze on renewable energy development or solar development in Illinois,” said Brian Granahan, chief legal counsel at the Illinois Power Agency. “It’s just that certain market segments have capacity open, while others, such as community solar, do not.”

Extreme demand for community solar caused snags for the adjustable block program almost directly out of the gate. Because it’s administered by a lottery system, most developers threw as many projects into the pot as they could. Granahan said the agency received about 900 community solar applications when it only had enough funding for about 120.

“There were companies that sunk...hundreds of thousands of dollars into project development in the state and didn’t get awarded a single project,” said Garrett Peterson, vice president of project development at commercial and community solar developer Pivot Energy. “That’s not a sustainable way to build an industry.”

The budget for the state’s purchase of renewable energy credits is set by a cost cap that cannot exceed about 2 percent of the 2007 price per kilowatt-hour paid by the state’s utility customers. The solar community sector is now hoping to increase that cap.

Pivot Energy won 11 community solar projects in the lottery, totaling about 31 megawatts (DC). But Peterson said the Colorado-based company is staring into a “big void for 2020,” because it can’t move forward on a large portion of the 75 projects it submitted to the adjustable block program.

“At the moment we have probably 50 permitted project sites throughout the state that are just sitting, and we’re obviously not the only developer in that scenario,” said Peterson. “We need to come up with a solution.”

The industry has decided on a preferred fix: It’s rallying behind a pair of bills currently in the legislature (HB 2966/SB 1781) called the “Path to 100.” The legislation would ramp the budget cap to 4 percent by 2030 but would not, despite its name, increase the RPS to 100 percent.

Legislators have also introduced another, more wide-reaching bill, the Clean Energy Jobs Act. That bill aims to expand renewables and associated jobs while enshrining a target of 100 percent renewables by 2050.

The latter effort is backed by environmental groups including the Sierra Club Illinois Chapter, clean energy advocates such as Advanced Energy Economy and labor groups including the SEIU 1, which represents 50,000 workers throughout the Midwest. But the solar industry prefers the narrower option.

“The Path to 100 is more directly aimed at supporting continued solar development and growth. We know that jobs will come as an ancillary benefit of that,” said Peterson. “What we really want to do is create a sustainable clear runway…so there aren’t stranded projects and sunk costs and developers left with uncertainty about the market.”

After Pritzker’s call for legislation last week, it’s not unlikely that new bills with similar remedies will crop up as Illinois enters its spring lawmaking session.

"Plenty of room left" for solar success

Within current constraints, Illinois has also logged several noteworthy solar successes. Though distributed solar has faced some stumbles, the Future Energy Jobs Act has spurred between 1,500 and 2,000 megawatts of large-scale solar, which Granahan calls “a great success story.” Those projects are still under development.

The state’s Illinois Solar For All program, which offers higher REC prices for projects that benefit low-income communities, has a budget structure that funds the program at about $30 million on an annual basis — meaning budget concerns don’t impact its continuation. Under the Clean Energy Jobs Act, the program would be greatly expanded.

And residential installers still have a considerable amount of spare capacity to work with, with their “blocks” barely dented. Jared McKenzie, CEO of Headline Solar, a residential company in the Chicago area, started his business in California before quickly moving it to Illinois to soak up the incentives.

“We have plenty of room left; commercial solar, not so much,” said McKenzie, who added that 2019 was a sort of “guinea pig year” for Illinois’ residential solar industry.

WoodMac projects the state will install nearly 87 megawatts of residential solar in 2020, increasing to 134 megawatts in 2021. The state narrowly registers in the top 10 state markets for residential installs, with analysts forecasting upside potential associated with the adjustable block program.

Based on Headline’s success in Illinois — the company is completing 20 to 30 installs per month only a year after its founding — McKenzie is considering expansion to states including Texas, Wisconsin and the Carolinas.

Despite those wins, the state isn’t close to reaching its renewable portfolio standard, or even its current goal of 16 percent in 2019 (though it is on track to acquire the quantitative amount of renewables the RPS requires, said Granahan). The primary reason the state is now falling short, according to Granahan, is simply because Illinois needs to build out a lot more renewable energy.

“Facilitating the development of that much new renewable energy generation would require additional funding that isn’t presently available,” he said.

But it appears a legislative fix upping that budget remains a priority for many, including the governor.